The Extraordinary Story In Part Of Greece & Greek Islands Art & Architecture & History:

Athens. The capital of Greece took its name from the goddess Athena, the goddess of wisdom and knowledge. Morning guided sightseeing tour of Athens. Tour includes the Royal Palace, the Olympic Stadium, the Temple of Jupiter, Hadrians Arch and Constitution Square. Constitution or Syntagma Square has a long history. It seems every major event in Greece's modern history has either been mourned or celebrated here. See the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier guarded by the elite soldier's chosen for their height and strength and time permitting, the changing of the guard. Visit the Acropolis to see the Parthenon. Built between 447 and 438 BC, it is the most important and characteristic monument of the ancient Greek civilization and still remains its international symbol. Discover the old quarter, the Plaka, which is huddled at the foot of the Acropolis and is the oldest section of the city and is a hodge-podge of narrow winding alleys, flower-filled courtyards, old balconied houses and marvelous lively cafes that is closed to automobile traffic. The streets are crammed full of the tourist shops and great restaurants.

The arts reflect the society that creates them. Nowhere is this truer than in the case of the ancient Greeks. Through their temples, sculpture, and pottery, the Greeks incorporated a fundamental principle of their culture: arete. To the Greeks, arete meant excellence and reaching one's full potential.

Ancient Greek art emphasized the importance and accomplishments of human beings. Even though much of Greek art was meant to honor the gods, those very gods were created in the image of humans.

Much artwork was government-sponsored and intended for public display. Therefore, art and architecture were a tremendous source of pride for citizens and could be found in various parts of the city. Typically, a city-state set aside a high-altitude portion of land for an acropolis, an important part of the city-state that was reserved for temples or palaces. The Greeks held religious ceremonies and festivals as well as significant political meetings on the acropolis.

Three different types of columns can be found in ancient Greek architecture. Whether the Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian style was used depended on the region and the purpose of the structure being built

Greek Excellence: The Acropolis

In ancient Athens, Pericles ordered the construction of several major temples on the acropolis. Among these was a temple, the Parthenon, which many consider the finest example of Greek architecture.

Built as a tribute to Athena, the goddess of wisdom for whom the city-state Athens was named, the Parthenon is a marvel of design, featuring massive columns contrasting with subtle details.

Many barely noticeable enhancements to the design of the Parthenon contribute to its overall beauty and balance. For example, each column is slightly wider in the middle than at its base and top. The columns are also spaced closer together near the corners of the temple and farther apart toward the middle. In addition, the temple's steps curve somewhat — lower on the sides and highest in the middle of each step.

Sadly, time has not treated the Parthenon well. In the 17th century, the Turks, who had conquered the Greeks, used the Parthenon to store ammunition. An accidental explosion left the Parthenon with no roof and in near ruin. In later years, tourists hauled away pieces of the Parthenon as vacation souvenirs.

Beauty in the Human Form

Ancient Greek sculptures were typically made of either stone or wood and very few of them survive to this day. Most Greek sculpture was of the freestanding, human form (even if the statue was of a god) and many sculptures were nudes. The Greeks saw beauty in the naked human body.

Early Greek statues called kouros were rigid and stood up straight. Over time, Greek statuary adopted a more natural, relaxed pose with hips thrust to one side, knees and arms slightly bent, and the head turned to one side.

Other sculptures depicted human action, especially athletics. A good example is Myron's Discus Thrower Another famous example is a sculpture of Artemis the huntress.

The piece, called "Diana of Versailles," depicts the goddess of the hunt reaching for an arrow while a stag leaps next to her.

Among the most famous Greek statues is the Venus de Milo, which was created in the second century B.C.E. The sculptor is unknown, though many art historians believe Praxiteles to have created the piece. This sculpture embodies the Greek ideal of beauty.

The ancient Greeks also painted, but very little of their work remains. The most enduring paintings were those found decorating ceramic pottery. Two major styles include red figure (against a black background) and black figure (against a red background) pottery. The pictures on the pottery often depicted heroic and tragic stories of gods and humans.

Thinkers

The citizens of Athens were fed up with the old "wise" man.

Socrates, one of ancient Greece's most learned philosophers, found himself on trial for his teachings. The prosecution accused Socrates of corrupting the youth of Athens. A jury of hundreds found Socrates guilty and sentenced him to death.

At the age of 70, Socrates willingly drank hemlock, a powerful poison that put an end to his controversial life. How did it happen that Athenians put to death a great philosopher such as Socrates?

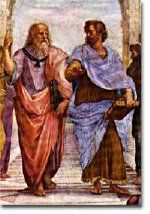

In the Renaissance artist, Raphael's School of Athens, Plato (shown on the left) argues that one should search for truth from above, while his pupil Aristotle argues that answers can be found through observation on Earth.

Throughout his entire life, Socrates questioned everything from Athenian government to Greek religion and the gods themselves. His ultimate goal was finding the truth, which he believed could be reached through reason and knowledge. Socrates was a teacher, but he did not have a classroom, any books, or even a school. Instead, Socrates lectured publicly. Anyone interested in what he had to say was invited to listen.

Socrates practiced a style of teaching that has since become known as the Socratic method. Essentially, Socrates taught through questioning. He started with simple questions, then progressed to more complex, deeper questions. Through the application of reason and logic, Socrates revealed answers to many questions that led to a greater understanding of the world.

Problems arose because Socrates often questioned the very fundamentals and traditions of Greek society. His constant questioning and searching for the truth were seen as dangerous by many and ultimately led to his death.

Plato's Republic

Plato, a student of Socrates, also achieved greatness as a philosopher. Unlike Socrates, however, Plato chose to write his ideas down. In one of his most renowned works, The Republic, Plato outlined his vision of the ideal state.

Surprisingly, Plato's republic was not very democratic. Plato was greatly disturbed at the way the mass of Athenians had agreed to put to death his brilliant teacher and mentor, Socrates. Plato believed that uneducated people should not have right to make important decisions for everyone.

Instead, Plato envisioned a society with many classes in which each class contributed what it could. In his ideal society, farmers grew the food for the republic, soldiers defended the republic, and a class of intelligent, educated philosophers ruled the republic. Not surprisingly, Plato lived at a time when democratic society in Athens was in decline.

One of Plato's students, Aristotle, also distinguished himself as a thinker. Aristotle wrote about and studied many subjects, including biology, physics, metaphysics, literature, ethics, logic, art, and more. He emphasized the importance of observation and the gathering of data.

Although Aristotle made important discoveries in many areas, his explanation concerning the movement of heavenly bodies was wrong. Aristotle believed that the Earth was the center of the universe, and that all heavenly bodies revolved around the Earth. This makes sense from a strictly observational standpoint. Looking up at the sky, it looked to Aristotle like everything (sun, moon, stars) circled the earth. In this case, Aristotle's reliance on observation led him astray. In reality, the Earth revolves on its own axis, causing the illusion of it being the center of everything.

A Golden Age of Thought

Besides the three great philosophers described above, ancient Greece produced many other important thinkers. In the realm of science, Hippocrates applied logic to the field of medicine and collected information on hundreds of patients. His work helped advance people's understanding of the causes of disease and death and swayed people from believing in supernatural reasons.

Greek thinkers applied logic to mathematics as well. Pythagoras deduced multiplication tables as well as the Pythagorean theorem relating to right triangles. Euclid revolutionized the field of geometry, and Archimedes worked with the force of gravity and invented an early form of calculus.

In the realm of the social sciences, Herodotus, is often credited with being the first modern historian. Another historian, Thucydides, tried to be as objective as possible in reporting the history he recorded.

Many of these advancements and revelations seem obvious by today's standards. But 2,500 years ago, most humans were concerned with providing food and protection for their families and little else. Most of them were ruled by kings or pharaohs who had supreme decision-making power. The Athenian democracy encouraged countless innovative thoughts among its citizens.

To the ancient Greeks, the thinking was serious business.

MENU

Helen's Greek Kitchen|All Rights Reserved/Web Customization Powered By CoreWeb Technologies LLC A Limited Liability Company